‘The great engineer of the universe has made man as perfectly as he could make him, and he could not have invented a better device for his maintenance than to provide him with a sense of pain.’– Leibnitz, 1969 (1)

Nobody knows my pain the way I do. Nobody knows how I feel inside when I bang my head or bite my tongue. You can certainly imagine – you can sympathise and think about your own experiences. But you cannot know how it feels to be me. And if you cannot know my physical pain, you certainly cannot know my emotional pain. You cannot know how I will feel when I fail an exam, break up with a partner of twenty years or come home after a difficult day. Ultimately, pain is a very lonely experience. And it is there for a reason.

The aim of the modern world has been to banish pain. There is an entire medical speciality aimed at reducing physical pain. It has allowed us to perform life-saving operations and transform decades of debilitation. But what I want to talk about is mental anguish and our path towards anaesthetising psychological suffering.

Again, reducing psychological pain is not in itself a bad thing. Indeed, some would argue that many of our problems lie in our underestimation of psychological pain and its impact on a person’s life; the loss of independence, loss of motivation, loss of relationships and a loss of life.

But there is a difference between alleviating severe psychological distress associated with deep, dark emotions and the emotions of everyday life.

Pain is a warning – it is a necessity. This is clearly illustrated in a very rare condition termed ‘Congenital Insensitivity to Pain’ in which patients are unable to feel pain. These patients often present with repeated bone fractures, unnoticed infections and repeated damage to tissues of the body. Let us correlate this with psychological pain. Mental suffering is just as vital to human growth as physical pain, and that our yearning to eradicate suffering in its entirety may be making us less human.

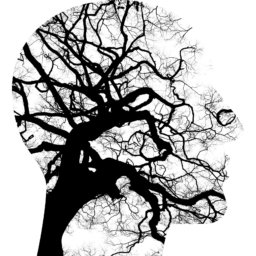

Pain transects the boundary between the biological, psychological, cultural and philosophical spheres. It is present within the nociceptors and local C fibres within our peripheral nerves, along the white matter of our spinothalamic tracts and in the somatosensory cortex of our brain. But it is also more than that. It is also present within our culture, telling us what is the ‘right’ way to feel pain.

Pain is subjective. How we see pain has an impact on how we react to it. In the modern era in which we see pain as a challenge a technological obstacle, we see it as a nuisance; something that must be gotten rid of, and quickly. Furthermore, we see pain as a biological process, and thus our answer to pain is the medical doctor. It is for the doctor to decide if our pain is ‘real’ or not. It is for them to decide if we require treatment, if there is an underlying issue or if it is ‘all in our heads.’ Pain that is linked to an underlying process such as a disease is valued more than pain that is psychological. One merely has to look at the stigma associated with Fibromyalgia or Irritable Bowel Disease; conditions in which we do not yet know the underlying physiological processes.

Our culture also tells us how to feel it and react to pain. Culture tells us whether it is the mother, father or both who must groan when a child is born. The environment we are in can completely mask pain that would otherwise be excruciating; injuries received during heroic acts are often not even felt. Studies of soldiers during World War II found that soldiers with horrific injuries at times did not even feel their pain, for their mind was placed elsewhere: I must get out of this battle. I must survive (3).

Some cultures tell us that pain is a part of life; that it is there to be experienced and may even lead to greater insights about the world. Buddhism’s philosophy on pain is particularly enlightening in this respect; if one can experience suffering without reacting to it, one can reach a higher level of being. If we see pain as meaningful then we do not consider it as something we need to conquer. Let us view this from another perspective: could we still feel happiness if we could no longer feel pain? How would we even know what happiness is – what would we compare it to? Would we still appreciate it? Pain is just as important in our lives as happiness and joy.

‘Progress in civilisation has become synonymous with the reduction of the sum total of suffering.’– Ivan Illich, 1976 (2)

From the outset the quest to eliminate all suffering sounds like a noble pursuit. But let us dig a little deeper: is our quest to maximise happiness or minimise pain? To minimise one would be to minimise the other. A reduced ability to feel pain would mean a reduced ability to feel happiness.

The Western World has been taken over by emotional painkillers. As we attempt to anaesthetise ourselves to reduce mental suffering, so we turn to stronger stimuli in an attempt to feel human again. Sex, drugs and rock & roll. Binges of TV shows, adrenaline-pumping activities, Internet gaming obsessions. We have anaesthetised ourselves to the point that we can no longer feel any emotion at all. We have become numb. We thus seek adrenaline through other venues; through hectic work lives, competitive & cut-throat atmospheres, late nights spent in the office, increasingly gory horror films and the desensitisation of violence.

What would a life of no emotional pain be like? Would it be bliss or numbness? Without pain we would not feel the joy of our first kiss or the nostalgia of our childhoods. To suffer is to live life to the fullest.

Forget my beloved childhood. Forget those years fighting pirates, those twilights racing through the streets.

Forget that first sip of alcohol, that sting that tore across the tissues of your tongue. Forget that first kiss, those soft, beautiful lips pressed gently against your own. Forget that feeling of being loved, of being held, of being wanted, of being heard.

Forget that feeling of joy, of gratitude, of tears running down my cheek.

Forget the warm hug of your fathers embrace twelve years after coming home.

Forget your mothers’ home-cooked pies, those rainy nights when she would lie by your side, her warmth glowing like an ever-lasting sun.

Forget that deep-seated anger curdling at the back of your tongue as you drag yourself through mind-numbing chores. Forget that intense agony, that hatred, that woefulness as you watch your peers climb the ladder rungs above you.

Forget your screaming, your shouting, your scarring and your pleading. Forget your howls and your whelps, your swallowed body shivering against the bedroom door as you tore apart your innards.

Forget the concern hidden behind that voice, that compassion, that understanding.

Forget all of that. Give me my cigarette and my beer. My television and my laptop. I do not want to suffer. I do not want to feel. I do not want to breathe. I do not want to live.

- Leibnitz, G.W. Essais de Theodicee sur la bonte de Dieu la liberte de l’homme et l’origine du mal. Paris: Garnier-Flammarion. 969. no. 342

- Illich, I. 1976. Limits to Medicine: Medical Nemesis – The Expropriation of Health. Marion Boyar.

- The Institute of Art and Ideas. Psychiatry and the Meaning of Pain [Online]. Available at: https://iai.tv/video/psychiatry-and-the-meaning-of-pain [Accessed 1st January 2019]

- Uskul, Ayse K. 2010. Socio-cultural aspects of health and illness. In: French, David and Kaptein, Ad A. and Vedhara, Kavita and Weinman, John, eds. Health psychology (2nd edition). Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 347-359. ISBN 978-1-4051-9460-0.

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here: angury.co.uk/the-culture-of-pain/ […]