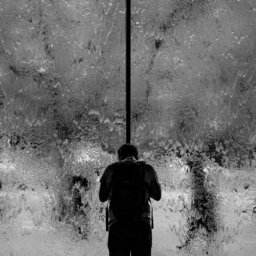

Since starting work in Psychiatry I have noticed an interesting phenomenon amongst the clinicians I work with; what I call ‘the blank face.’ The blank face is a communication tool that is used when psychiatrists speak to their patients. They sap all emotion out of their face and take up an air of apathy. They maintain this facade for as long as the patient remains in the room, like a puppet whose strings have become detached. They remain in the same position like a statue sculpted from stone. They do not smile, they do not frown, they do not relax. They remain in this trance until the patient gets up and leaves, as if they are playing a character in a play.

I spoke about this with one of my consultants a few weeks into my first rotation. He described it as a blank slate, a way of neutralising your body language to allow your patient to project their emotions onto you; anger, hatred, despair, joy, sadness. It encouraged patients to open up about themselves without fear or judgement or scrutiny, he told me.

I then spoke about this with the patients. Or rather, they spoke about it with me. They voiced their frustration and anger at being treated as if they weren’t human, like their experiences and feelings did not matter. They felt as if they weren’t being taken seriously and their story was one the doctor had heard time and time again – like it wasn’t important. They felt like they were being treated like an object rather than a person.

Transference is a psychoanalytic term coined by Freud. It refers to an unconscious process in psychoanalysis during which the patient transfers their feelings, thoughts and desires from a previous, early relationship onto the therapist in the present moment (1). This process is thought to give the therapist a unique insight into their patient’s early relationships; experiences which would otherwise have been unknown to the patient (2). By recognising and interpreting this transference, the therapist can then assist the patient to understand the origins of their behaviour in their current relationships and mould them in a way that is more helpful for them. Thus, the more objective and ‘blank faced’ the therapist, the greater the likelihood of the transference developing within a neutral setting rather than, say, the patient merely reacting to the therapist’s own emotions that are displayed (2). It also changes the therapist (and the psychiatrist) into a robot.

Talking about your emotions is a red flag in Medicine; talking about the emotions that a patient provokes within you is an even bigger red flag. As clinicians we are expected to be walking pieces of plastic, with patients distress and tears sliding off our skin. In Psychiatry our patients’ emotions can be particularly intense as we deal with people who experience difficult and unmanageable emotions on a regular basis. Freud advised that one should maintain an emotional distance in the face of such distress in the name of objectivity and warned that to do otherwise would result in one becoming swept up in the patient’s desires (2). The problem, is that this goes against everything that it means to be human.

Critics argue that the blank face goes against the very idea of forming a therapeutic alliance with a patient; rather, the ideal therapeutic relationship should be one in which two people are seen as human beings bringing their own life experiences to the room (2). The idea of the blank face can even be seductive to some therapists who may use it as a way of avoiding their own difficulties and emotions that they experience, preferring to place all responsibility on the patient and gaining enjoyment in the omnipotent character they play in their patients lives (2).

Some have pointed out that the aim of the blank face is impossible, for the very act of the therapeutic relationship creates a reciprocal human relationship (3) which cannot simply be reduced into an exercise of emotions being flung into the stone face of the psychiatrist. Yet this is exactly what is expected in psychiatric training, with much of the focus being on a check-list of symptoms that add up to a patient’s mild, moderate or severe depressive disorder, as if the psychiatrist themselves have no impact on the relationship that is being formed in the room at that very moment. Yet the presence of the doctor can in itself be therapeutic – or the very opposite.

In fact, the blank face can be downright dangerous; Szasz referred to it as patient abuse (1). It is through one’s emotional response to one’s patients and their stories that one shows care, compassion and understanding (3); this is illustrated by the countless patients I have met who have repeatedly told me how misunderstood and ignored they have felt by mental health services. The blank face can turn the therapeutic relationship on its head; patients who may have experienced little care and warmth in their early life and are seeking understanding and empathy may instead come up against a blank face, bringing with it a shame and confusion, thus devaluing the potential relationship that could have formed between patient and clinician (3). Indeed, if any of us were to open up to a professional about the deepest aspects of our lives only to be met by a blank face, our initial reaction would likely be one of embarrassment and hostility.

What is missing from this understanding is the idea that the therapist – and the psychiatrist – plays an active role in the relationship with the patient. They are not a blank screen but a human being, bringing with them their own training, life experience and emotions to the relationship (1); to ignore this is to do a disservice to one’s patients.

This is not to say that transference is not helpful to understand and interpret. Studies show that transference-focused therapy can help to improve quality of life in those with emotionally unstable personality disorder and that transference can bring helpful insights to the patient than enable them to facilitate changes in their lives and current relationships (1) (3); it cannot be ignored. It can give greater control to the patient by helping them to understand why they behave the way that they do within relationships and, if interpretations are offered in the correct way and at the correct time, can deepen the therapeutic alliance (1). But it does not mean that the therapist must act as a passive receptacle to receive this transference from the patient like an aerial.

There is thus a balance to be had between allowing the transference to develop within the therapeutic relationship and recognise and understand it accordingly, and to develop a genuine and authentic relationship with ones patients whilst recognising one’s own emotions that are brought to the encounter, which are not seen as an obstacle but a way of facilitating communication and empathy.

References

- 1. Suszek H., Wener E., Maliszewski N. 2015. Transference and its usefulness in psychotherapy in the light of empirical evidence. Roczniki Psychologiczne. 3: 363-380

- 2. Yalom I. Existential Psychotherapy. 1st edn. United States of America: Basic Books; 1980. Chapter 9: Existential Isolation and Psychotherapy; p411-413.

- 3. Handley N. 1995. The Concept of Transference: A Critique. British Journal of Psychotherapy. 12: 49-59.